Higher Education Access and Health Outcomes Among Undocumented Immigrants

- Olivia Kim

- Nov 14, 2022

- 3 min read

There are over 427,000 undocumented immigrants enrolled in higher education in the U.S., and nearly 90% of them attend college as opposed to vocational school [1]. However, it is estimated that almost 1.6 of the 11 million undocumented immigrants in the U.S. are between ages of 16 to 24 years old [2]. In addition to greater socioeconomic opportunities, higher education is especially critical because many studies have found it to be a strong predictor of health outcomes.

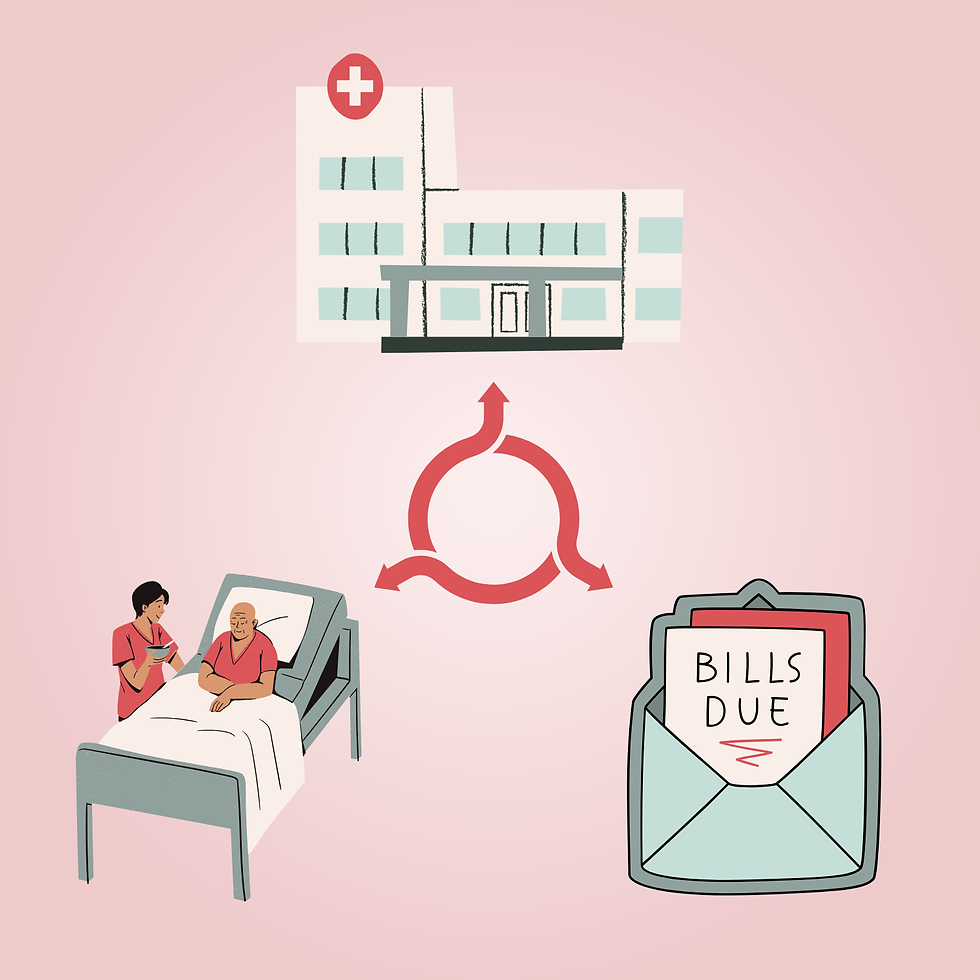

Documentation status has been identified as a social driver of health and risk factor: those without legal documentation status are more likely to have worsened health [3]. Among non-senior adults that are noncitizens in the U.S., 42% were uninsured in 2020 [4]. This lack of healthcare coverage for undocumented adults leaves many of them only able to access healthcare through Emergency Departments (EDs), Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs), and local volunteer-run clinics [5]. Another way undocumented immigrants receive care is through clinics on college campuses. Most colleges in the U.S. require students to have health insurance and likely provide subsidized plans, so higher education is a great mechanism in which undocumented immigrants may achieve better health outcomes in the short and long term.

DACA is instrumental in providing undocumented students access to higher education since attendance in higher education is a major qualifying factor for DACA recipients [5]. DACA provides a mechanism in which undocumented children may reach higher education and improve their social drivers of health. The program also relieves stressors that are generated from fear of being deported. However, those who are DACA recipients are not qualified for health insurance through the ACA, meaning they are ineligible for Medicaid and CHIP [5]. Another program that is key for young adults to achieve citizenship is the DREAM act, which permits those who have grown up in the U.S. to apply for temporary legal status and eventually become eligible for citizenship if they go to college or serve in the military. Studies have found that having a protected legal framework like DACA and DREAM leads directly to better health outcomes by bettering economic stability, increasing educational opportunities, and increasing healthcare access [6].

It is imperative that undocumented immigrants be provided the opportunity to get higher education for both immediate access to clinical care and improved long-run health outcomes. However, more can be done to support college students without legal documentation status.

Undocumented immigrants in college face a myriad of challenges and stressors, leading them to be at a higher risk for behavioral health issues. These stressors include, but are not limited to, inability to finance required textbooks, fear of performing poorly academically and being removed from the DREAM act, and concerns for one’s future and financial stability [3]. A study found that COVID-19 had a profound impact on dreamers’ mental health, more so than documented students [7]. It was identified that out of those in the study, “47% of the dreamers met the clinical cutoff for anxiety, 63% met the cutoff for depression, and 67% (2 in 3) met the cutoff for anxiety and/or depression.” Id.

Programs such as DACA and DREAM need to be protected to continue access to higher education and healthcare, but it is also important that on-campus care for undocumented immigrants includes mental health resources and financial support systems.

Edited by: Sam Shi

Graphic Designed by: Shanzeh Sheikh

References

National Data on Immigrant Students. Higher Ed Immigration Portal. (2022, November 4). Retrieved November 9, 2022, from https://www.higheredimmigrationportal.org/national/national-data/

Profile of the unauthorized population - US. Migration Policy Institute. (2022, October 1). Retrieved November 9, 2022, from https://www.migrationpolicy.org/data/unauthorized-immigrant-population/state/US

Enriquez, L.E., Morales Hernandez, M. & Ro, A. Deconstructing Immigrant Illegality: A Mixed-Methods Investigation of Stress and Health Among Undocumented College Students. Race Soc Probl 10, 193–208 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12552-018-9242-4

Published: Apr 06, 2022. (2022, April 6). Health Coverage of Immigrants. KFF. Retrieved November 9, 2022, from https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/fact-sheet/health-coverage-of-immigrants/

Adams, C. (2018, December 13). How Increased Access To Higher-Ed Improves Health Outcomes for Undocumented Immigrants. University of Michigan School of Public Health. Retrieved November 7, 2022, from https://sph.umich.edu/pursuit/2018posts/higher_ed_undocumented_immigrants.html#:~:text=Bachelor's%20Student%2C%20Public%20Health%20Sciences&text=Additionally%2C%20undocumented%20immigrants%20can%20typically,education%20strongly%20influence%20these%20barriers.

Sudhinaraset, M., To, T. M., Ling, I., Melo, J., & Chavarin, J. (2017). The Influence of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals on Undocumented Asian and Pacific Islander Young Adults: Through a Social Determinants of Health Lens. The Journal of adolescent health : official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 60(6), 741–746. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.01.008

Goodman, J., Wang, S. X., Ornelas, R. A. G., & Santana, M. H. (2020, January 1). Mental health of undocumented college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. medRxiv. Retrieved November 9, 2022, from https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.09.28.20203489v1.full

Comments