Hospital Overflow is Far From Over: Patients Are Returning to Regular Care on Top of COVID-19 Influx

- Abby Cortez

- Nov 10, 2021

- 3 min read

For nearly two years, the COVID-19 pandemic has overwhelmed hospitals across the country. The mass influx of patients took its toll on things like resources and nurses. But coronavirus patients weren’t the only people sick in 2020; they were just the only ones seeking care. The CDC reported that 41% of American adults delayed or simply avoided medical care due to the pandemic. Some even avoided basic care and screenings. In Austin, Texas mammograms were down 90%, and according to TIME, about 15% of Americans skipped specialist appointments like cardiologists. These are concerning numbers considering cancer and heart conditions are deadly; what’s further concerning is that as many as 12% of those patients did not seek emergency care.

Even though it might seem counterintuitive to avoid seeing a doctor in an emergency, there was, and remains, a very real fear of infection. Especially prior to the development of a vaccine, COVID-19 posed a great and virtually unpredictable risk to patients, especially those with underlying conditions. Hospitals, though working to keep everything sterile, were full of patients capable of spreading the infection. If fear of a life-threatening virus wasn’t enough to keep people out of hospitals, finance also played a role. Quarantine put a lot of people out of a job, and with that, left many without health insurance. So even if people mustered the courage to risk an appointment, many would have a hard time affording it.

Unfortunately, but perhaps predictably, this kind of concern adversely impacts low-income and ethnic or racial minority groups. These groups are not only more likely to have underlying conditions that need repeated care, but they are also more likely to be unable to afford it. Families barely able to afford the treatment they already need are not going to want to risk having to pay for coronavirus care on top of their usual medical expenses. Telehealth options are often presented as a way to help people worried about going in person for medical services, but this solution isn’t perfect. Not only is there a certain intimacy and connection that telehealth lacks, but for low income groups, telehealth may not be a viable option.

A TIME study also revealed that the number of patients seeking care for mental health has also decreased. And though suicide rates didn't appear to increase during the pandemic, depression and anxiety rates certainly did. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, 4 in 10 adults experienced anxiety or depression during the COVID-19 outbreak, a fairly dramatic increase from the 1 in 10 it was prior to 2020. It’s concerning that a number of adults had to let go of mental health as a priority. The effect of this still remains to be seen as the pandemic continues.

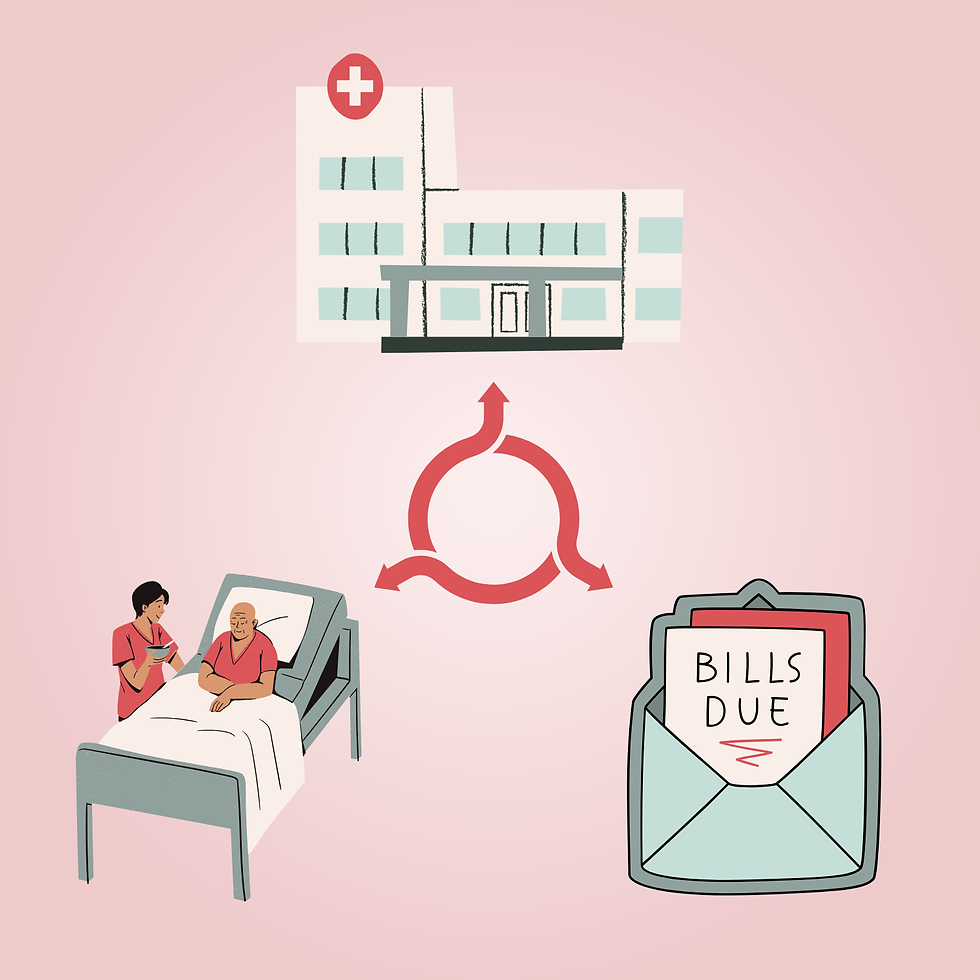

Not only does putting off medical care negatively impact patients, who may miss out on early diagnosis and treatment, but it also hurts hospitals. Much of hospital revenue comes from the procedures and appointments they have on a daily basis. When the pandemic put a stop to those kinds of patients, many hospitals saw their profits plunge. The financial losses to healthcare systems, in addition to the shortage of nurses and resources associated with COVID patients, is likely to have long lasting effects even as the pandemic begins to subside.

Hospitals and patients have not had adequate time to recover from the effects of putting off medical care. A lack of vaccination rates and resurgence in coronavirus cases following the delta variant have once again put stress on hospitals. And even if more Americans get vaccines, there’s still a chance hospitals will remain overwhelmed, this time not with COVID patients, but patients now desperate for the care they put off.

Edited by: Olivia Ares

Graphic Designed by: Eugene Cho

References

Comments