Who Pays, Who Participates, and Who Benefits? Women’s Health in the Hidden Economy of Research

- Aditi Avinash

- Nov 17, 2025

- 4 min read

Most patients will never read the fine print at the end of a research article and will not see who wrote the grants, which company supplied the drug, or which committee approved the protocol, yet these quiet details shape who is invited into research, whose data are collected, and which bodies are considered too complicated or too risky to include. The result is an invisible economy in which funding streams, ethical guidelines, and institutional habits determine what knowledge medicine produces. Women’s health sits at the center of this problem, since questions about who funds research and how conflicts of interest are managed intersect directly with decisions about who is permitted to participate in clinical trials, especially people who can become pregnant, who are pregnant, or who are lactating. Together, these forces dictate not only what gets discovered, but also who is ultimately able to benefit from those discoveries.

The Money Behind the Medicine

Research depends on grants, infrastructure, and institutional support, and as Mandal and colleagues explain, funding can come from internal sources or from outside organizations such as governments, corporations, and nongovernmental groups, a mix that is never ethically neutral [1]. When sponsors have commercial interests in the outcome, pressure to produce favorable findings can shape which questions are asked and how results are presented, and hidden relationships or incomplete conflict-of-interest disclosure can weaken trust in scientific work. Mandal et al. argue for transparency and oversight rather than rejection of industry involvement, insisting that institutions and researchers manage funds responsibly and disclose how sponsorship may shape a study [1]. For women’s health, these concerns are especially important because funders who view pregnancy, lactation, or hormonal conditions as legally risky or scientifically inconvenient may avoid trials that include these groups, which limits the evidence base needed to care for patients whose physiology has long been understudied.

From Exclusion to Conditional Inclusion

Women, particularly those who were pregnant or could become pregnant, were historically excluded from research. ACOG traces this pattern to harms such as the thalidomide tragedy, after which regulators barred people of childbearing potential from many trials in an attempt to protect future children [2]. This approach meant that drugs were tested almost entirely in nonpregnant bodies and then prescribed during pregnancy with little direct evidence to support their safety.

ACOG’s 2024 Committee Statement reframes this exclusion as an ethical failure rather than a safeguard. It argues that people who can become pregnant, who are pregnant, who are lactating, or who identify as women should be presumed eligible for research and that their inclusion is a matter of justice [2]. When these groups are left out, the benefits of research are distributed unfairly and the risks shift to patients who must make decisions without reliable data. Exclusion does not remove risk but instead relocates it, since clinicians still have to prescribe medications during pregnancy and often must rely on estimation rather than evidence.

Autonomy and the Conditions Placed on Participation

Ethics committees and funding bodies often impose conditions such as mandatory contraception or extra consent requirements, and ACOG argues that when these rules apply only to people who can become pregnant, they are paternalistic and discriminatory because they imply that one group’s autonomy is less trustworthy than others [2]. This creates a distribution problem as well as a procedural one. When restrictive criteria determine which studies receive funding, pregnant and lactating people are often excluded from participation, which means the evidence base skews toward nonpregnant bodies and later shapes clinical guidelines and insurance coverage.

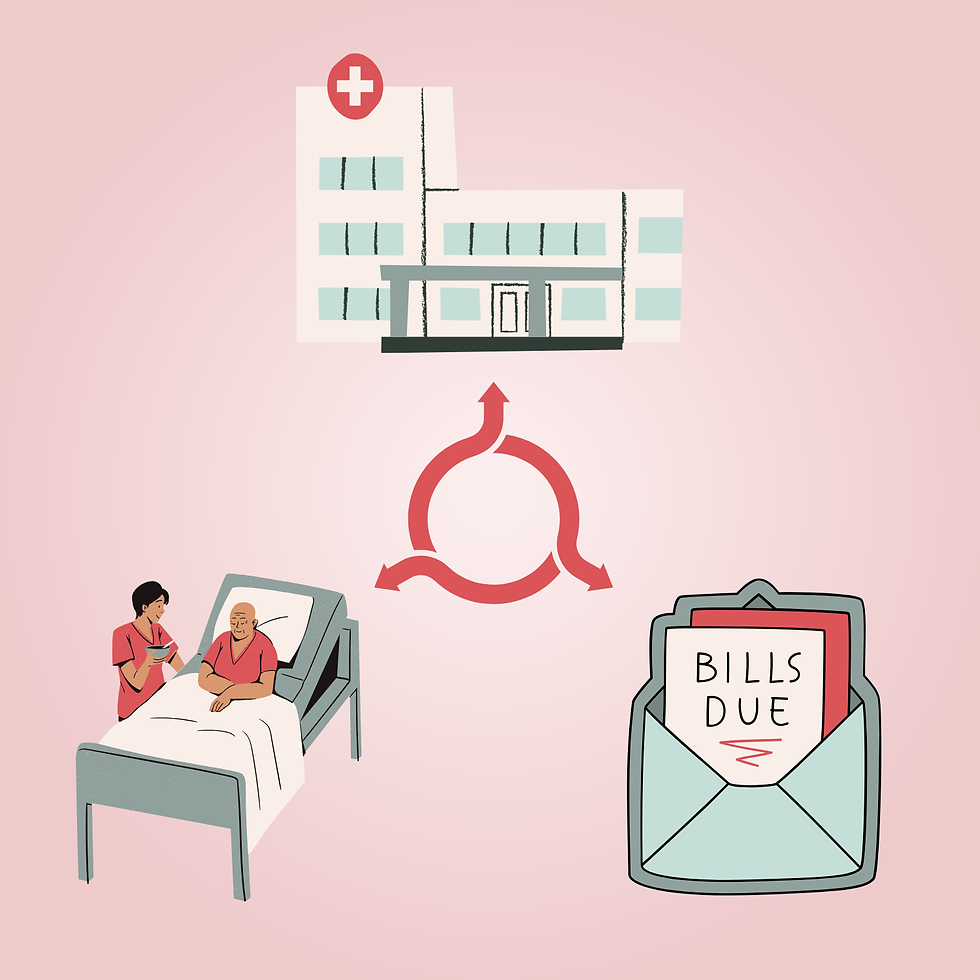

Mandal et al. point out that funding structures influence how research questions are framed, while ACOG shows how ethical rules around inclusion and consent can either reinforce or challenge those pressures [1, 2]. Together they reveal a cycle in which funding influences protocol design, protocol design determines who can participate, and participation patterns shape which bodies medicine understands and knows how to treat.

Reimagining an Ethical Research Economy for Women’s Health

When pregnant or lactating people are systematically excluded from research, clinicians frequently must improvise when treating asthma, depression, autoimmune disease, or pregnancy-specific complications. This improvisation can lead to extra visits, off-label prescribing, and higher costs. The financial burden that patients experience often reflects earlier decisions made by grant reviewers and ethics committees.

A more ethical research landscape would place justice, transparency, and respect for participants at the center of funding decisions. Mandal et al. remind us that every source of support requires clear oversight and honest disclosure [1], while ACOG shows that people who can become pregnant should be actively included in studies rather than sidelined [2]. The hidden economy of medicine is ultimately about whose experiences shape scientific knowledge and whose needs are left unsupported. If research is to serve all patients, the choices made long before a study begins must reflect that responsibility.

Designed by: Julia Williams

References:

[1] Mandal, J., Parija, M., & Parija, S. C. (2012). Ethics of funding of research. Tropical parasitology, 2(2), 89–90. https://doi.org/10.4103/2229-5070.105172

[2] American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Ethical considerations for increasing inclusivity in research participants. Committee Statement No. 9. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2024;143:e155–63.

Comments