Financial Hurdles in Medical Technology

- Pranav Kannan

- Nov 17, 2025

- 3 min read

When a new surgical device in the OR gets FDA approved, it sounds like the end of the medtech

innovation journey. In reality, it’s only the point where the science part ends and the money part begins.

To actually appear in patient care and on a hospital bill, the device must pass through multiple quality

control gates.

Stage 1: The FDA gate

The FDA’s job is to determine whether a device is safe and effective for sale [1,2,3]. Most devices reach the market through three pathways. A 510(k) submission shows that the device is equivalent to an existing device in the market [1]. A De Novo is used for novel low- to moderate-risk devices that don't have a predecessor, so it employs a risk-based review [2]. Finally, Premarket approval (PMA) is reserved for high-risk medical devices and requires the most extensive research to be approved [3].

These are not just labels; they also correspond to product development costs. An economic analysis found that bringing a device to market through the 510(k) pathway costs approximately $31 million on average, while a high-risk PMA costs around $94 million [4,5]. Most of the spending is tied directly to FDA related testing stages, such as bench, human factors, and clinical studies. Early phases can be supported by grants through the National Institutes of Health (NIH); however, later stages are usually financed by investors who expect to recover their costs once medical devices are used in procedures [6].

Stage 2: The payer gate

FDA approval alone doesn’t guarantee that anyone will pay for the device. US reimbursement is vital to the medical device market and comprises three key facets: coverage, coding, and payment [7,8].

Coverage: Inquires whether Medicare/Medicaid or private insurers will cover the device or procedure, and if this product is medically necessary. [7,8,16]

Coding: asks whether the device and procedure used can be recorded on a claim form using systems such as Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes for services and HCPCS codes for devices and supplies.[7-10]

Payment: determines how much money flows when specific codes are used [7,8,16]

If any one of these pieces is missing from device proposals, the device can be clinically excellent and FDA cleared, but it will rarely be used, and hospitals cannot cover their costs.

A recent example of this process is the application of AI/ML methods in medicine. The FDA now lists

hundreds of AL/ML devices authorized for marketing; however, adoption in everyday practice is uneven,

and numerous policy discussions highlight limited reimbursement as a significant barrier to use [11-16].

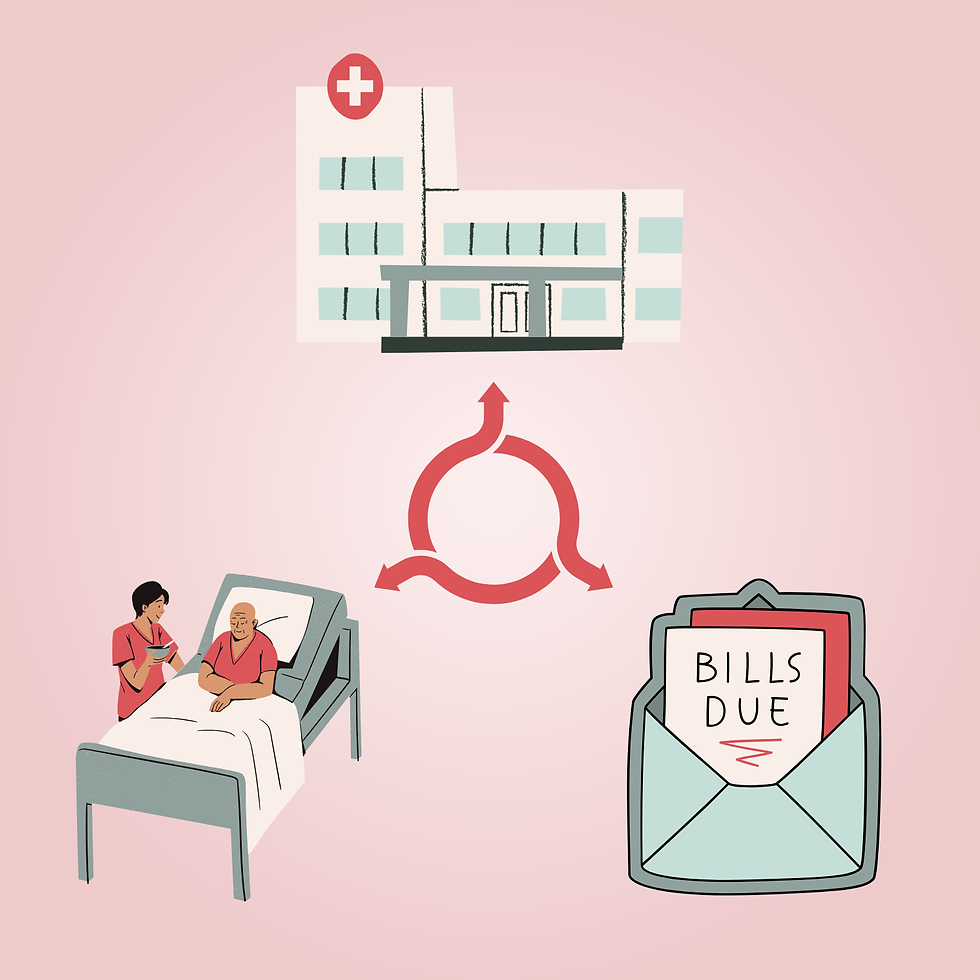

Grants and investors fund the evidence needed for an FDA review, after which the FDA decides which

devices can be approved for the market. Finally, CMS (Medicare/Medicaid) and private insurers

determine which devices can be realistically used in hospitals. In the end, what reaches the OR isn’t just

what works in the lab, but what survives this financial and regulatory marathon from grant to bill.

Designed by: Julia Williams

References:

[1] U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (n.d.). Premarket Notification (510(k)). https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/premarket-submissions-selecting-and-preparing-correct-sub

mission/premarket-notification-510k

[2] U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (n.d.). De Novo Classification Request. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/premarket-submissions/de-novo-classification-request

[3] National Institutes of Health (NIH), SEED. (n.d.). FDA Authorization for High-Risk or Novel Devices. https://seed.nih.gov

[4] StarFish Medical. (n.d.). How Much Does It Cost to Develop a Medical Device? https://starfishmedical.com

[5] Focused Ultrasound Foundation. (n.d.). Why It Takes So Long to Develop a Medical Technology –Part 14. https://www.fusfoundation.org

[6] National Institutes of Health (NIH), SEED. (n.d.). Small Business Program Basics: Understanding SBIR and STTR. https://seed.nih.gov

[7] National Institutes of Health (NIH), SEED. (n.d.). Reimbursement Knowledge Guide for Medical Devices. https://seed.nih.gov

[8] Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (n.d.). CMS Guide for Medical Technology Companies and Other Interested Parties. https://www.cms.gov

[9] American Medical Association. (n.d.). CPT® Overview and Code Approval. https://www.ama-assn.org

[10] Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (n.d.). Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS). https://www.cms.gov

[11] U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (n.d.). Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning (AI/ML)-Enabled Medical Devices. https://www.fda.gov

[12] Joshi, G., et al. (2024). FDA-approved artificial intelligence and machine-learning-enabled medical devices: An updated landscape. Electronics, 13(4), 498. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics13040498

[13] Muralidharan, V., et al. (2024). A scoping review of reporting gaps in FDA-approved AI devices. PubMed Central (PMC). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc

[14] Wu, K., et al. (2024). Characterizing the clinical adoption of medical AI devices using real-world Medicare claims. NEJM AI. https://ai.nejm.org

[15] Adler-Milstein, J., et al. (2024). Meeting the moment: Addressing barriers and facilitating clinical adoption of artificial intelligence in medical diagnosis. National Academy of Medicine. https://nam.edu

[16] Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. (2024). Paying for software technologies in Medicare: Report to the Congress. https://www.medpac.gov

Comments